Chapter Four: An Affordable And Attainable Way Of Achieving The Boudoir

To understand the power of a boudoir cap, one has to consider the physical space it is named after. In her work on the meaning of boudoir caps in New Zealand, Webster argues that buying and wearing a boudoir cap was an act of symbolic consumption which made the idea of the boudoir accessible to all (Webster, 165). What actually was a boudoir and what was its role in the life of women at the beginning of the twentieth century? The boudoir as a concept is mentioned in numerous books written for women to inform them about interior design or a recommended beauty regimen. These documents suggest that the boudoir was understood as a real physical space but also as an attitude towards a room. As such it relates to certain activities which are deemed quintessentially feminine.

When giving interior design advice on The Bedroom and Boudoir Lady Barker did not make a real distinction between the two rooms and claims that the bedrooms furnished according to her advice already possessed “a certain element of the […] boudoir” (Barker, 87). In the 1878 novel Une page d’amour the French novelist Zola describes how a cook waiting for her fiancé is able to fabricate a boudoir feeling in the kitchen by dimming the light with a curtain and scenting the room (1975 Winkler Verlag translation, 110). In her book on beauty treatments Mme Bayard defined the space by the activities a woman practises there. Her list included studying fashion, arranging dress and hair, and shaping nails – a place where a woman “by every artificial appliance at her command, does all her care and taste can suggest to add new lustre to her natural charms” (Bayard, 9). While the boudoir was imagined as a feminine and even seductive space, it was also a room that only few houses actually possessed. The great majority of women did not have the space of the financial means to have a real boudoir. But wearing a boudoir cap enabled them to add that same glamour to their lives. The boudoir cap was an affordable, portable and wearable form of the boudoir.

Early advertsing photographs of a model wearing a Spirella corset and boudoir cap

Date: c. 1914-1920

Origin: Great Britain

Photos used with permission from The Garden City Collection.

These photographs were created for advertising purposes and depict an idealised boudoir. The elaborate dressing table is decorated with a lace table cloth, a floral arrangement and a silver set of two hair brushes and a mirror. In other images, a decorative screen and floor length mirror further allude to this being a space for studying fashion and beauty treatments. Whilst it was unlikely many of Spirella’s target customers had access to such a space, advertising photos certainly helped them to buy into the fantasy of the boudoir.

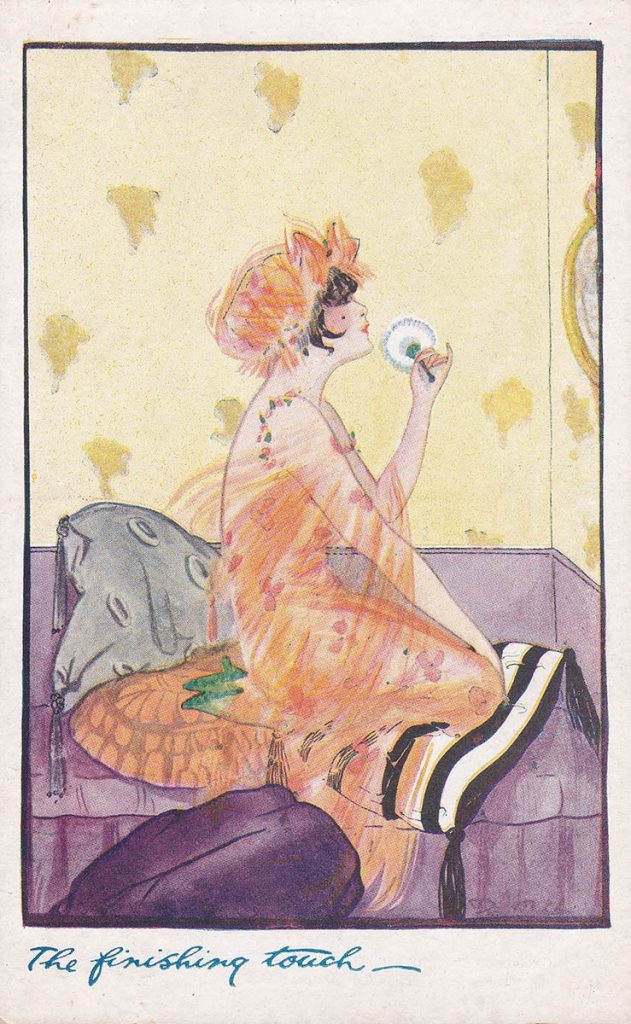

'The Finishing Touch' Boudoir Postcard By The Photochrom Co

Date: c. 1920s

Origin: Great Britain

Brand: The Photochrom Co Ltd

Glamorous boudoirs were not just part of advertising campaigns but also depicted in illustrations like this postcard. It shows a ‘flapper girl’ at her toilette applying finishing powder. She is wearing a diaphanous lingerie robe and a matching boudoir cap decorated with an oversized bow. The sheer fabric reveals the outlines of her figure showing how the boudoir was connected to erotic ideas.

This understanding is further supported by the visible attributes that the design of the cap shares with ideas about the ideally decorated boudoir space. The colours and decorative elements which American interior designer de Wolfe described for her own personal boudoir in 1913 correspond with the visuals that were common in contemporary boudoir caps. She depicted walls painted in ‘egg-shell blue-green’ with ‘ivory white’ woodwork and assures the reader that “there is always a possibility for rose-red in [her] rooms” (de Wolfe, 165f). While de Wolfe herself spoke critically of the boudoir cap, the glamorous and feminine space she envisioned appears to be perfectly captured in the design of contemporary boudoir caps. The colours ivory white and shell blue were common boudoir colours during the Edwardian period and remained so into the 1930s. And her touch of rose-red parallels the rosebud trimming which Mannin remembered “was considered very fetching on a boudoir cap.” (Mannin, 70). For women of lesser financial means the boudoir cap was a much more realistic way of emulating an upper-class life of leisure. Through this lingerie garment social aspirations could be acted out and temporarily achieved.

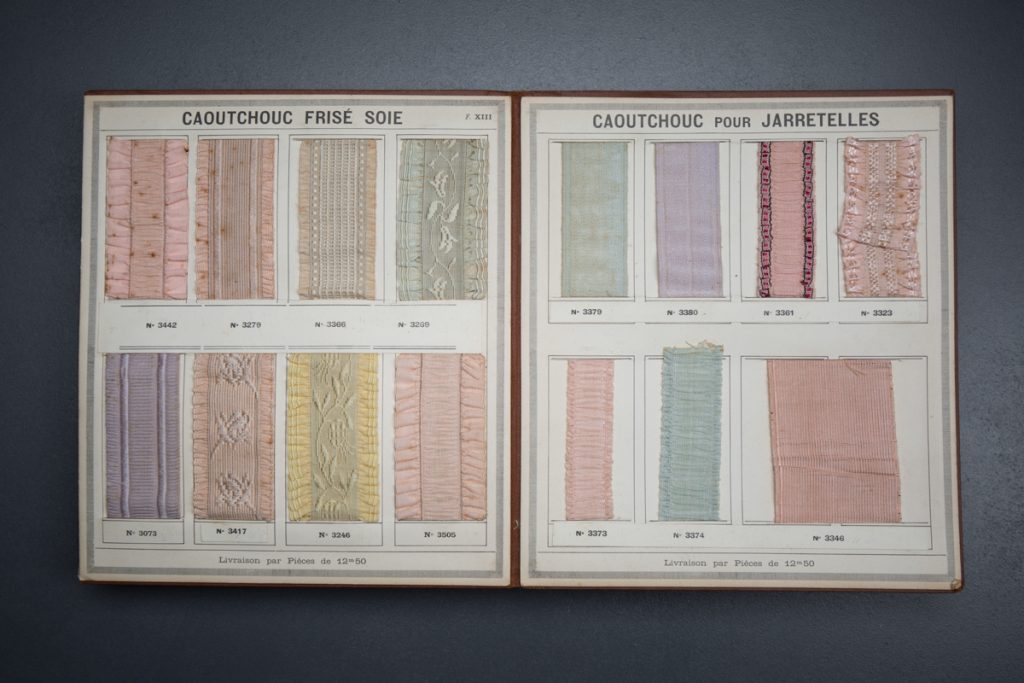

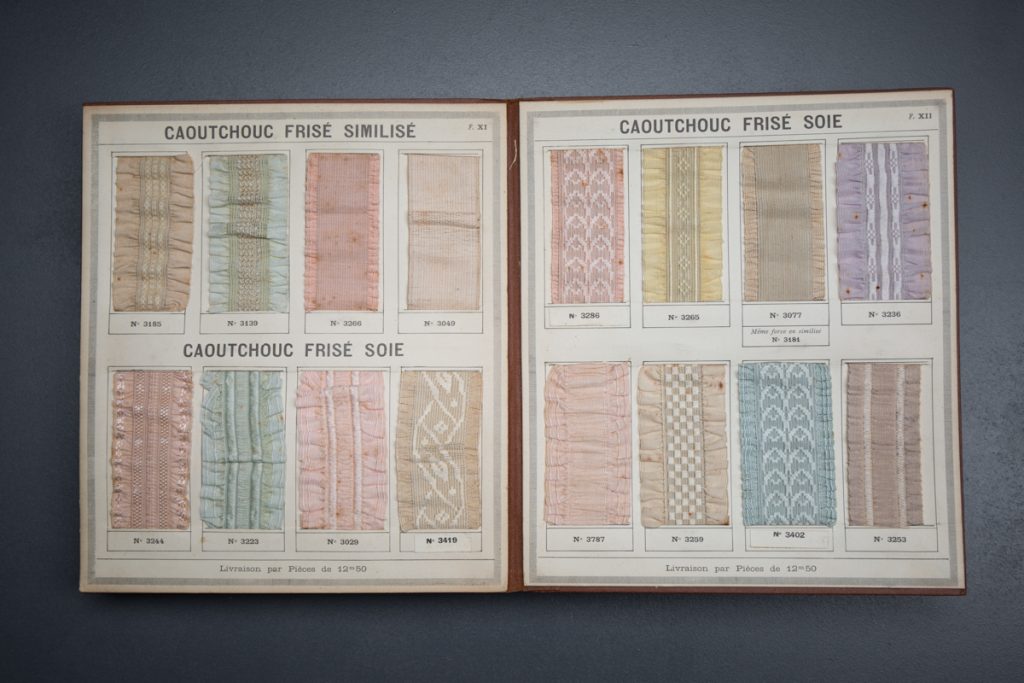

'Lacets Et Tissus Elastiques No 23' Elastic Trim Catalogue

Date: c.1900s

Origin: France

Fabric: Elastics

A sample book of various elastic trims c. 1900. Elastication was still a relatively new technology, and these trim options offered makers of all varieties of clothing exciting possibilities. Elaborate frilly silk elastics were commonly used in lingerie and corsetry, mostly for garters and suspender straps. The examples in this book are notably intricate, with silk frills and woven patterns.

The colour palette of this catalogue typifies the Edwardian boudoir colour scheme ideal; egg shell blue and pale pink dominate the catalogue, with other pastel tones such as lilac and pale yellow also making an appearance. The beige shades were likely originally ivory, but have been faded and stained by the passage of time.

Navigation

Chapter One: Introduction & The Boudoir Cap’s Predecessors

Chapter Two: A Rite Of Passage Into Adulthood

Chapter Three: Glamour For All

Chapter Four: An Affordable And Attainable Way Of Achieving The Boudoir

Chapter Five: A Safe Version Of Sex Appeal

Chapter Seven: Dress For Undressing