Chapter Three: Glamour For All

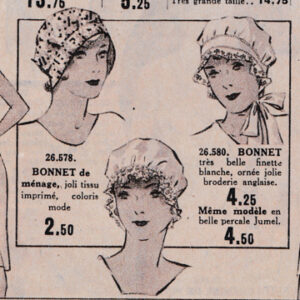

Caps were offered at a great variety of price-points and while one could buy them at luxury department stores, many publications catering towards a female audience included instructions or patterns on how to make them at home. In 1927 for example The Manchester Guardian printed instructions on how to embroider a crêpe-de-Chine boudoir cap in cross-stitch which they promised would give “a quick and effective as well as dainty result” (Manchester Guardian, 13 Sep 1927, 6). In her autobiography Ethel Mannin remembered that “a few yards of narrow lace and ribbon and a bit of net” were enough to make one for yourself (Mannin, 70).

In their work on English undergarments the Cunningtons discuss ‘class distinctions’ as one of the roles of underwear (Cunnington, 14). Boudoir caps are an exception here since they were actively blurring class distinctions. While they were associated with the upper classes who could afford to buy them and who had the rooms in which to wear them, women of lower status with lesser financial means were still able to wear them. Caps helped these women practice ‘elegant economy’ and dress in ways that would cost little but create the illusion of wealth.

Lace, Tulle & Lace Boudoir Cap By Au Bon Marché

Date: c. 1910s

Origin: France

Fabric: Tulle and lace

Brand: Au Bon Marché

This boudoir cap has a base of delicate cotton tulle, panelled with graphically seamed leavers lace trims. A yellow silk bow trims the rear of the cap, with appliquéd silk ribbon roses forming circle motifs on both sides of the head. The attached paper tag at the rear of the cap states that the garment came from Au Bon Marché, a Parisian department store, from the ‘veils and ornaments’ department. The rear of this tag asks the customer: ‘please do not remove this essential label, in case of exchange or return’. It also contains space for the identification number of the saleswoman, date and stock number.

Au Bon Marché was founded in 1838 in Paris as an early department store, originally selling a range of goods such as haberdashery and umbrellas. The store still exists today and is owned by the LVMH corporation, now specialising in luxury goods.

Silk Habotai & Lace Boudoir Cap With Silk Rosettes

Date:c.1920s

Origin: Great Britain

Fabric: Silk habotai and lace

Brand: Custom made

A boudoir cap made of an ecru leavers lace with panels of pale pink silk habotai. It is embellished with silk rosettes at the back and sides of the head. This variety of leavers lace would have likely been intended to be cut down to strips of trim, but has instead been used as a fabric.

The creative and at times unexpected use of materials can be often seen in handmade boudoir caps as many women used the materials they had at hand.

Navigation

Chapter One: Introduction & The Boudoir Cap’s Predecessors

Chapter Two: A Rite Of Passage Into Adulthood

Chapter Three: Glamour For All

Chapter Four: An Affordable And Attainable Way Of Achieving The Boudoir

Chapter Five: A Safe Version Of Sex Appeal

Chapter Seven: Dress For Undressing