Chapter Two: Setting The Stage - Bal Tabarin

Cabaret emerged in 1880s Paris as a vibrant blend of music, dance, comedy, and theater, flourishing in the bohemian Montmartre district. Folies Bergère became a popular nightlife spot after its opening in 1869, and the Moulin Rouge, which opened in 1889, quickly became an icon of this lively culture. As one observer quipped, “Montmartre music halls have become the fashion,” offering revelers a spirited alternative to the theater. In 1904, composer Auguste Bosc opened Bal Tabarin, a dazzling new Art Nouveau venue that soon rivaled its neighbors. As journalist Reginald Wright Kauffman described it in 1920, “The Bal Tabarin was a world of its own, with its own etiquette.”

In 1928, Pierre Sandrini and Pierre Dubout took over, and made Bal Tabarin the home of Sandrini’s spectacular French cancan, a dynamic fusion of Parisian dance-hall flair and British and American chorus-line precision. The venue remained a hub of Parisian nightlife throughout the 1930s and the now-illustrious designer Erté joined their costume team in 1933. During the Second World War, Bal Tabarin briefly acted as a soup kitchen for out-of-work performers until it was reopened and frequented by German officers during the Nazi occupation of Paris. Although it officially closed in 1953 and was demolished in 1966, Bal Tabarin endures as a memory of Parisian nightlife, rowdy performances, and daring costumes.

Located at 36 rue Victor-Massé in the 9th arrondissement, the original Bal Tabarin building epitomized the height of the Art Nouveau style, largely taking inspiration from the sinuous aspects of the natural world. This 1914 photograph shows how the building’s facade features unruly “whiplash” motifs, especially around doors and windows, and mascaron (face) ornaments. The motif at the top of the archway is an Ancient Greek lyre, used here to symbolize music.

The interior of the Bal Tabarin building was decorated with frescoes by Adolphe Léon Willette. Willette is credited as an architect of the famous cabaret, the Moulin Rouge, which opened in 1889. The frescos can be seen in this 1907 illustration, among many formally-dressed men and women dressed in “pigeon-breasted” silhouettes. The fashionable crowd appears to watch a spectacle featuring nude or semi-nude female performers.

With its exaggerated brushstrokes, this expressionist painting by French artist Louis Abel-Truchet captures a lively quadrille at the Bal Tabarin in 1906. The quadrille is a social dance, first introduced in France around 1760. It was also performed at the Moulin Rogue, where daring performers delighted spectators by dancing among them. Elegantly dressed women are seated in the foreground, wearing stylish picture hats and carrying large brisé fans.

One 1905 article published in the British illustrated magazine The King and His Navy and Army commented that of the four professional quadrille dancers then employed at Bal Tabarin, two were of mixed African and European ancestry. The publication included this photograph, taken by prolific Polish cabaret photographer Walery, appearing to show three of the four young women. Over the twentieth century, the Black population in Paris grew due to its vibrant cultural scene and different—though still racialized—attitudes toward Black performers compared to the United States. A 1904 Bal Tabarin poster evokes racist tropes reminiscent of American minstrel imagery.

In his memoir A Jayhawker in Europe, American author William Yoast Morgan recalled that when Moulin Rouge performers danced the quadrille, their kicks were so high that he saw “the most wonderful display of things that are put in store windows at home and marked ‘white goods sale’ or ‘lingerie.’” Elements of the quadrille evolved into the cancan during the nineteenth century, which became a signature dance of Parisian cabarets. Its high kicks and energetic movements are depicted by Julius Paulsen in this 1909 painting Bal Tabarin.

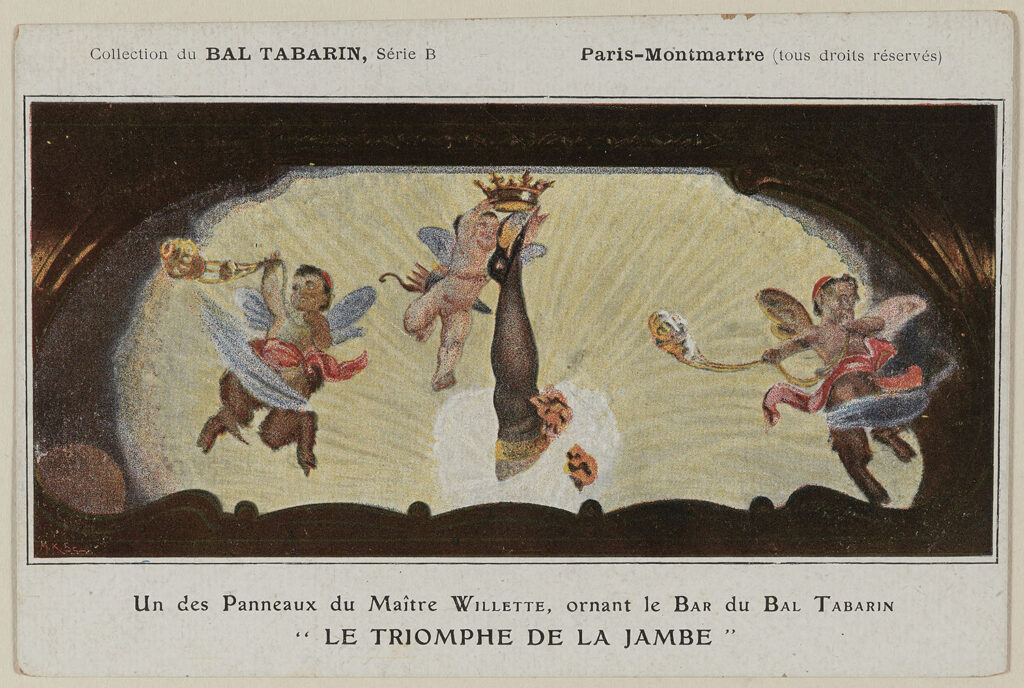

Among Willette’s original frescoes for the interior of Bal Tabarin was a female dancer’s leg, clad in a black silk stocking and ruffled garter, being crowned by a winged cherub. The cheeky painting was a clear reference to the venue’s famed quadrille and cancan dancers who revealed feminine limbs that were rarely seen in other contexts. Though barely visible above the bar in the 1907 illustration by Luceil (above), the fresco has been reproduced in this postcard, titled “The Triumph Of The Leg.”

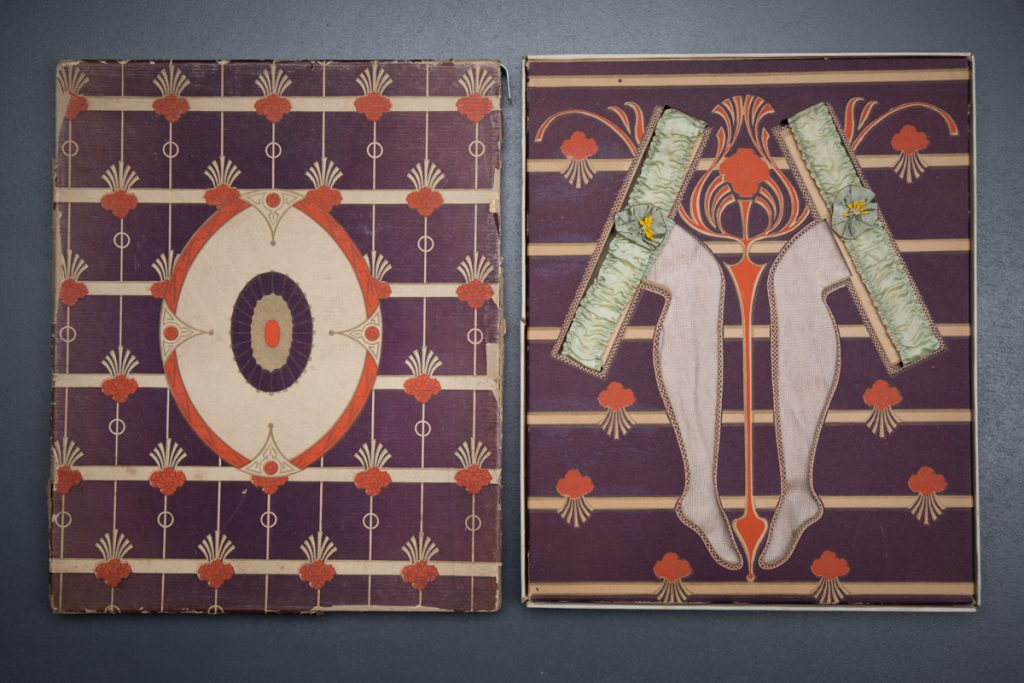

Ribbon Garter & Silk Stocking Gift Set

Date: c. 1920s

Origin: Great Britain

Fabric: Silk

Ladies’ legs were usually hidden under ankle-length skirts throughout the Belle Époque, making their appearance at cabarets like Bal Tabarin quite risqué. However, they were no longer a shocking sight by the 1920s, when this Art-Nouveau style garter and stocking gift set, reminiscent of Willette’s fresco, was created. American writer Harold Everett Porter commented in 1924: “the Bal Tabarin continues to advertise the cancan, because foreigners suppose it to be naughty … It simply demonstrates that ladies don’t run on casters – which most of us have known for some time.”

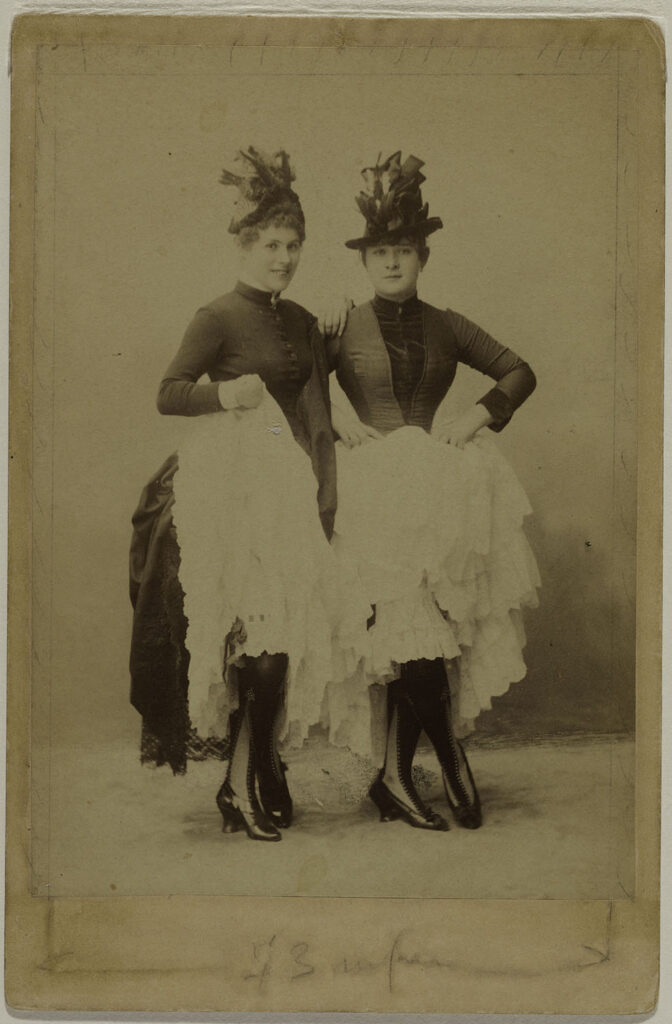

Lingerie played a major role in the spectacle of the cancan. In fact, to American dancer Blanche Deyo, it seemed like the entire point of the dance: shelaimed in 1906 that it was “mainly the swishing of skirts and lingerie.” As such, in 1875, an American newspaper warned women not to lend men their opera glasses when a cancan troupe came to town. This 1886 photograph shows two famous French cancan dancers, known by stage names La Goulue (meaning The Glutton) and Grille d’égout (meaning Sewer Grate), showing off their ruffled petticoats, drawers with ribbons, and fancy stockings.

Hand Stitched Cotton Lawn Open Drawers With Valenciennes Lace & Pin Tucks

Date: c. 1900s

Fabric: Cotton Lawn

During the 19th century, the cancan gained an international reputation for being obscene, even leading to arrests when dancers were found to be performing indecent acts. Although this indecency largely stemmed from the overt display of women’s petticoats and legs, the dancers’ high kicks would also reveal their genitals if they wore standard drawers like these. Women’s drawers were generally made without joining the seams in the crotch, as a functional necessity for relieving oneself when wearing multiple layers of long skirts. Photographs and artistic depictions of female cancan dancers from the late nineteenth century show them wearing drawers with closed crotches, which would have been created as a dance costume.

By 1923, Bal Tabarin was open daily and functioned as a dancehall until 12:30 a.m., when the cabaret opened, and closed at 4 a.m. This 1920s postcard shows “The Triumph of Venus,” a procession of skantily-clad performers in costumes inspired by Ancient Greece, complimented by the illuminated lyre motifs decorating the building interior. The topless model portraying Venus wears a panty brief much more revealing than standard 1920s underwear. The state of the building’s decor suggests that it was taken prior to 1928, when Bal Tabarin came under new ownership.

This 1937 video shows Bal Tabarin’s later Art Deco makeover, which replaced its outdated Art Nouveau interiors. At this time, wealthy Americans were known to frequent Bal Tabarin in the evenings to watch the cancan, which was reportedly “still a Tabarin specialty.” Americans such as famous fashion editor Diana Vreeland and author Katherine Anne Porter frequented this riotous scene during the 1930s, which was highlighted in both American and British fashion magazines. It was during this period that Erté began contributing costumes for Bal Tabarin.

In 1940, almost one year into the Second World War, Harper’s Bazaar announced: “There’s No Can-Can Now At The Bal Tabarin.” Germany had attacked France one month prior and began their occupation of Paris on June 14th. However, Bal Tabarin had actually ceased performances the year earlier. As of January 1940, Bal Tabarin acted as a canteen or soup kitchen for actors who found themselves out of work due to the outbreak of war. Vogue reported, “The Cancan dancers wear white aprons and wait on the other out-of-work actors.”

![Cabarets parisiens [le Bal Tabarin], 1914. Via Wikimedia Commons. Cabarets parisiens [le Bal Tabarin], 1914. Via Wikimedia Commons.](https://underpinningsmuseum.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Cabarets-parisiens-le-Bal-Tabarin1914.-Via-Wikimedia-Commons.-web-1024x739.jpg)