Date: 1956

Origin: France

Brand: Jacques Fath, Charmis, Christian Dior, Marie Rose Lebigot

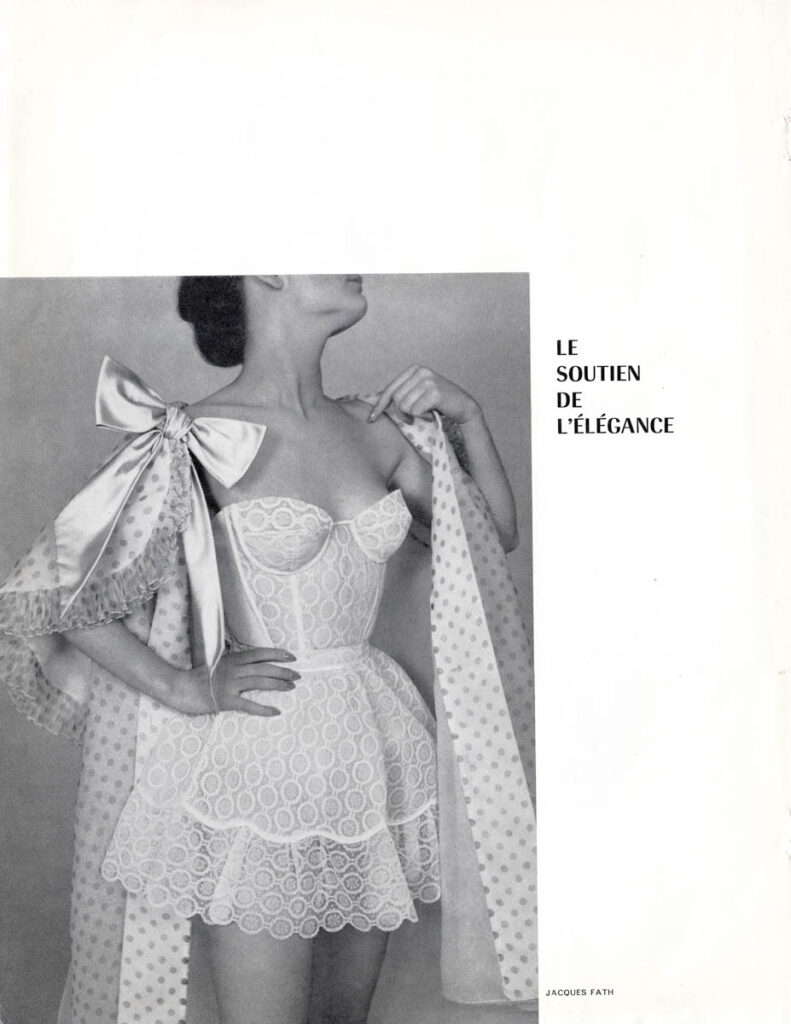

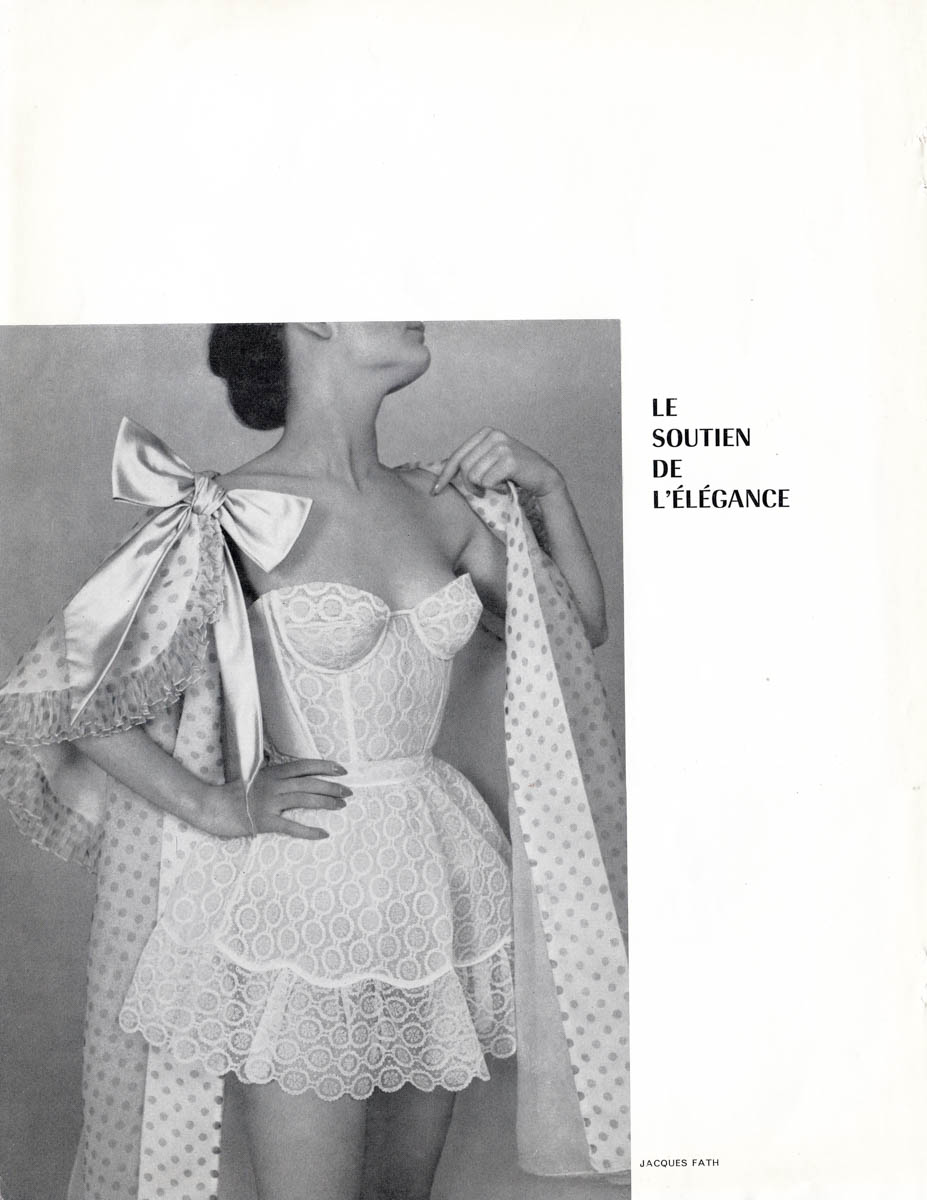

This is a French magazine excerpt titled Le Soutien de l’Élégance, or The Support of Elegance. This title carries a double meaning as it suggests both the idea of upholding elegance and the physical support offered by foundation garments, as in the French word soutien-gorge, which means “bra.” This excerpt is from 1956 and features foundation garments from Jacques Fath, Charmis, Christian Dior, and Marie-Rose Lebigot.

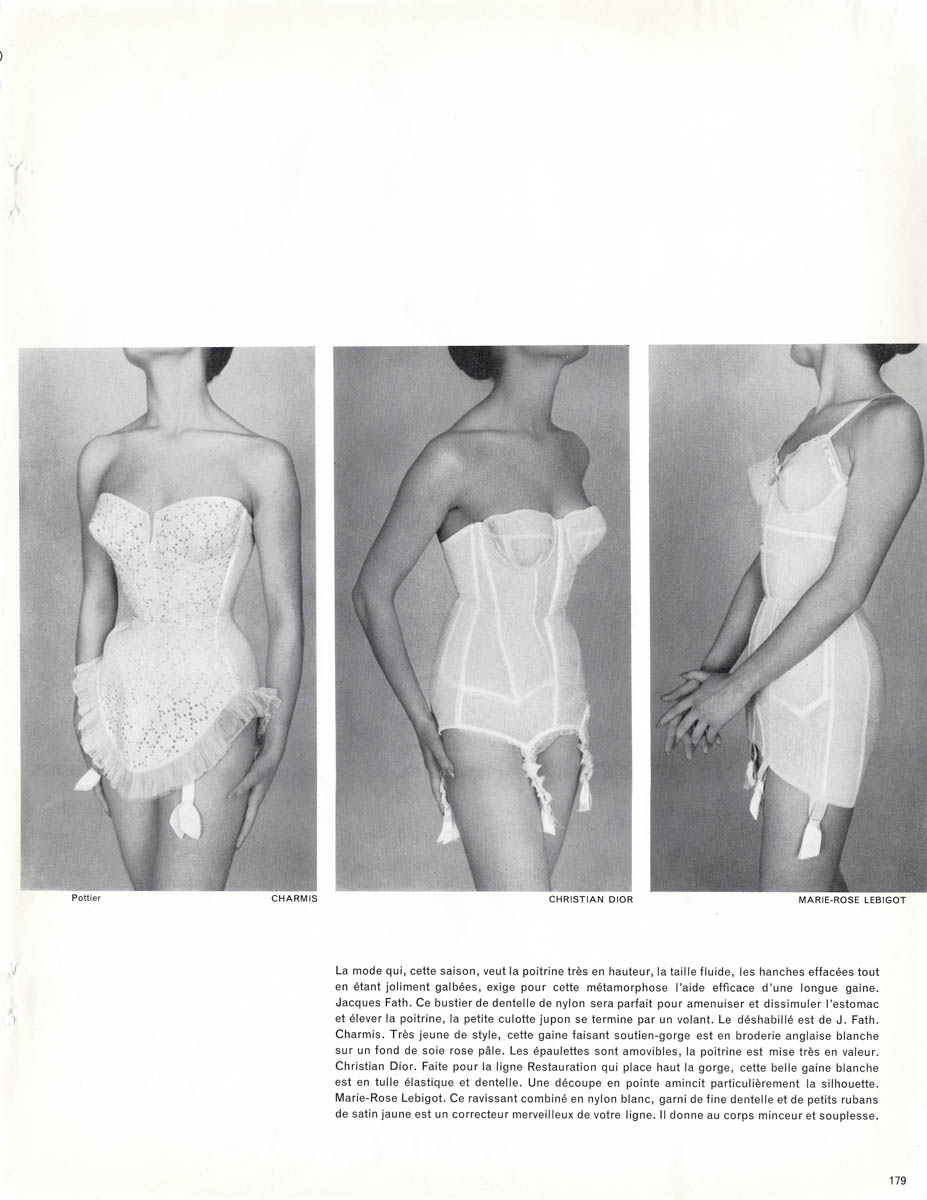

There is a short description for each garment with an intro that reads, “Fashion, this season, calls for a very high bust, a fluid waist, and hips that are smoothed yet beautifully contoured. Achieving this transformation requires the effective support of a long girdle” (translated from the French). The first garment, a nylon lace bustier by Jacques Fath is described as, “perfect for slimming and concealing the stomach while lifting the bust. The petticoat-style panties are finished with a ruffle.” Also made of nylon lace and from the same era, a pale pink bra by Jacques Fath is part of the Underpinnings Museum’s collection.

The following garment is a girdle with a built-in bra by Charmis that is described as ‘youthful’ and ‘made of white eyelet embroidery over a pale pink silk background.’ The shoulder straps are removable, and the bust is highly accentuated. Another Charmis foundation garment, a black corselet from 1955, is part of the Underpinnings Museum’s collection. Though differing in color and construction, both pieces reflect the brand’s attention to detail and structured support. The girdle features removable straps and a dramatically accentuated bust, while the corselet has an unusual design, with boning that stops at the waist rather than extending over the hips. Charmis was a notable French undergarment brand active from at least the late 1920s through the 1950s. Founded by a distinguished corsetière known as Madame Charmis, the label gained a reputation in the 1930s for refined and fashion-forward foundation garments. A 1933 issue of French Vogue references Madame Charmis by name, suggesting her status as a recognized designer during this period. By the mid-1950s, the brand was reportedly run by Madame Germaine Goutte. The clientele was said to include glamorous figures like Marlene Dietrich.

The next garment is by Christian Dior. The description translates to, “Made for the Restoration line, which lifts the bust high, this beautiful white girdle is crafted from elastic tulle and lace. A pointed cut (or V-shaped panel at center front) particularly slims the silhouette.” A Charmis girdle from ‘Dans La Haute Corseterie’ Magazine Editorial in the Underpinnings Museum’s collection has a similar pointed front panel to slim the waist. Dior’s Restoration line (“ligne Restauration”) appears to draw inspiration from the French Restauration period (approximately 1815–1830), a time of political upheaval marked by the return of the Bourbon monarchy after Napoleon’s fall. This era saw ongoing struggles between royalist and revolutionary ideals, as well as cultural shifts such as the rise of French Romanticism. Fashion evolved accordingly, moving away from the neoclassical Empire silhouette toward structured bodices, cinched waists, and fuller skirts—elements that closely align with Dior’s signature hourglass designs. A description of his Spring/Summer 1951 collection explicitly references Restauration influences, noting sharply tailored jackets, peplum details, and voluminous skirts that exuded historical elegance.

The last garment is by Marie-Rose Lebigot and has a description that reads, “this delightful white nylon corselet, adorned with fine lace and small yellow satin ribbons, is a marvelous figure-enhancer. It gives the body both slenderness and flexibility.” Although no longer well-known today, Marie-Rose Lebigot was a world-renowned corsetiere in the mid-twentieth century. She learned everything about corsetry from her mother, who was the original founder of her foundation garment business. Lebigot apprenticed under her mother who taught her anatomy, sculpture, and painting as a child and how to apply these subjects to designing for the female form. Marie-Rose took over the company in the early 1930s, and by 1951, was creating custom foundation garments for the presentations of famous Parisian couturiers, Paquin, Fath, Heim, and Lecomte, among others. In 1951, she was introduced to American consumers when she became affiliated with Lily of France, for whom she created brassieres and girdles. Lily of France was the sole distributor of Lebigot’s designs, which were all made in Paris. Additionally, Lebigot’s work was featured in several French films, including Êdouard et Caroline (1951), where she designed lingerie, and Casque d’Or (1952), where she was credited as the corset designer. She was among the designers experimenting with lingerie that enhanced the bust, a trend that gained prominence in the mid-20th century, and reportedly collaborated with Madame Carven on a push-up bra design, though others were exploring similar innovations, including Frederick Mellinger of Frederick’s of Hollywood.

Even ten years after the debut of Dior’s New Look, its influence still lingered in 1957. However, the silhouette was beginning to shift. Designers in Paris embraced a softer, more fluid approach to dressing, one that prioritized ease of movement and a casual elegance. Structured waists gave way to loosely belted shapes, while skirts swayed rather than flared, with fullness created by lightweight fabrics rather than stiff underpinnings. Even Dior, once synonymous with a more rigid silhouette, presented a sailor-inspired ensemble that twisted gently through the waist, a sign that fashion was loosening up. This evolution marked the end of what many consider the “golden age” of haute couture, and set the stage for a younger, more relaxed sensibility that would define the decade to come.

From the collection of The Underpinnings Museum.

Many thanks to Ellen Greene for the object description and research.